Pêche Profonde : Quel est le problème ?

En résumé

Il est clairement établi grâce aux recherches réalisées dans l’Atlantique Nord et dans le Pacifique Sud que les chaluts de fond détruisent pratiquement toutes les grandes espèces non ciblées, perturbent les couches supérieures des sédiments (les panneaux peuvent laisser des sillons faisant jusqu’à un mètre de profondeur dans les sédiments meubles) et plus généralement, produisent des habitats pauvres en biomasse et en espèces. Tous les chaluts prélèvent les organismes de façon non sélective, mais les chaluts profonds sont en outre extrêmement lourds. Ils raclent ainsi le fond sur de longues distances avec une force considérable. L’océan profond est généralement un environnement peu perturbé naturellement : les courants y sont faibles et les tempêtes qui se déroulent en surface y ont peu d’incidence, en conséquence de quoi, les organismes de constitution gélatineuse ou légère peuvent parfois atteindre de grandes tailles. Les organismes d’eaux profondes ne font donc pas le poids face à la masse et la vitesse des chaluts de fond.

Une analyse récente (Priede et al., 2010) résume ainsi les impacts associés au chalut de fond : « Il est bien établi que les pêches chalutières ont un effet mécanique direct sur les fonds marins par le biais d’une destruction des fonds, du prélèvement de coraux et d’invertébrés benthiques ». Cette étude a montré qu’en raison de la mobilité des poissons, l’impact des flottes chalutières sur les espèces ciblées, comme sur les espèces non ciblées, ne se limitait pas comme on le pensait jusqu’à présent, aux effets directs et mécaniques décrits plus haut. Les chercheurs ont ainsi calculé que la pêche chalutière, particulièrement française et ciblant notamment le sabre noir (mentionné dans la publicité) dans l’Atlantique Nord-Est, avait mené au déclin de l’abondance des poissons jusqu’à 2500 mètres de profondeur alors que les navires ne pêchaient que jusqu’à 1500 mètres. En outre, la zone de pêche a été estimée à 52 000 km2 mais l’étude a montré que l’impact des pêches s’étendait sans doute à une zone de 142 000 km2.

La seule façon pour qu’une pêcherie en eaux profondes soit durable d’un point de vue écosystémique est d’avoir un impact faible sur les écosystèmes. Or les chaluts de fond ne sont pas discriminatoires et causent des dommages irréversibles à l’écosystème. Ainsi aucune pêcherie au chalut profond ne pourra jamais répondre pleinement aux objectifs internationaux de durabilité des stocks de poissons et de préservation des habitats. Éviter systématiquement les chaluts impactant les fonds marins pourrait être une règle globale pour toutes les pêcheries d’eaux profondes.

Texte en partie tiré de la synthèse du workshop organisé par BLOOM sur la pêche profonde (Cliquez ici)

Une vision faussée des océans

En 1914, A. B. Alexander et ses collègues furent les premiers à étudier l’impact de la pêche sur l’environnement marin. Ils conclurent que « les chaluts à panneaux ne perturbent pas sérieusement les fonds sur lesquels ils sont déployés, ni ne les dénudent matériellement des des organismes qui servent, directement ou indirectement, de nourriture pour les pêcheries commerciales. » Ces propos reflètent à quel point les chercheurs de la première moitié du XXème siècle sont encore sous l’impression résumée par cette citation célèbre du biologiste anglais Thomas Huxley : « Toutes les grandes pêcheries maritimes constituent des ressources inépuisables » (1883).

La recherche sur les impacts des pêches

Depuis, les méthodes de recherche se sont améliorées mais elles ne se préoccupent réellement des impacts de la pêche qu’à partir des années 1970, au moment où les pêcheries de la Nouvelle Angleterre ou celles de la Mer du Nord (hareng) se sont effondrées. Le professeur Les Watling de l’université de Hawaii indique qu’il existe actuellement environ 250 études démontrant l’impact du chalutage sur les habitats, les espèces et la structure des communautés contre une poignée d’analyses montrant que cet impact peut être acceptable dans certaines circonstances. Par exemple dans un contexte de perturbation naturelle très élevée, ajouter la pression du chalut à celle de l’environnement ne fait pas de grande différence, « mais ces lieux sont très rares » précise Les Watling.

Des méthodes de pêche utilisées en grande profondeur (chalutage, filets maillants et palangres), ce sont les effets du chalutage qui ont été les plus évalués, quantitativement et qualitativement.

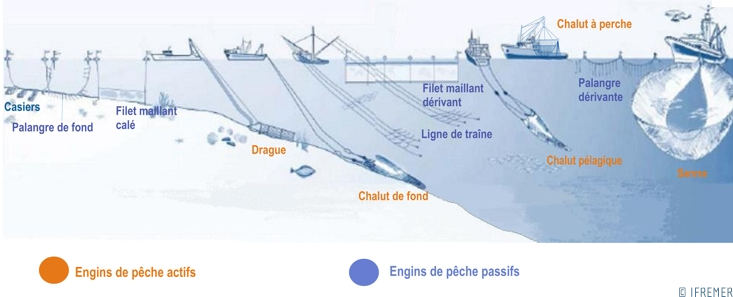

Les différentes méthodes de pêche

Les méthodes de pêche modernes sont très diverses, allant d’activités déployées uniquement dans les eaux de surface comme la drague (sorte de râteau) pour les coquilles, les moules, les praires, en passant par les nasses et les casiers ciblant les crabes, les filets maillants (ou filets droits), la palangre, le chalutage ou la seine déployés en pleine eau ou sur le plateau continental. Le chalutage en eaux profondes se déploie essentiellement sur les marges continentales du talus ou sur les pentes des monts sous-marins. Les méthodes de pêche actives (autrement désignées sous le nom d’arts « traînants ») sont les plus impactantes pour l’environnement marin, à l’inverse des arts « dormants », constituées d’engins passifs.

De toutes les méthodes de pêche, le chalutage de fond est aujourd’hui considéré comme la méthode de pêche la plus destructrice pour les écosystèmes et la biodiversité en raison de la surface qu’elle couvre au cours d’un trait de chalut et du fait que l’engin de pêche est en contact quasi constant avec le fond, où la majorité de la vie marine se trouve.

Le chalut : l’engin le plus destructeur de tous

Le chalut est l’engin le plus largement utilisé par les flottes hauturières profondes. Il représente 80% des méthodes de pêche profonde. En 2004, le Programme des Nations Unies pour l’Environnement (UNEP) a déclaré le chalut l’engin le plus destructeur d’entre tous :

“Active gear that comes into contact with the seafloor is considered the greatest threat to cold-water coral reefs and includes bottom trawls, dredges, bottom-set gillnets, bottom-set longlines, and pots and traps…Due to their widespread use, bottom trawls have the largest disruptive impact of any fishing gear on the seabed in general and especially on coral ecosystems.”

Une publication datant de 2003 classe les engins de pêche en fonction du degré de sévérité des impacts collatéraux qu’ils génèrent. Ceux-ci sont définis par les prises accessoires et la destruction de l’habitat.

Sur une échelle de 0 à 100, l’étude accorde :

- 30 à la palangre benthique

- 36 à la palangre pélagique

- 38 aux nasses et casiers

- 63 aux filets maillants pélagiques

- 67 aux dragues

- 73 aux filets maillants benthiques

- 91 aux chaluts de fond (ceux utilisés en surface, l’étude n’a pas considéré le chalut profond, or celui-ci pose des problèmes encore plus aigus).

Références

- Worldwide review of bottom fisheries in the high seas, FAO Fisheries and Aquaculture Technical Paper 522, 2008.

- UNEP 2004 – Freiwald, A., Fosså, J.H., Koslow, T., Roberts, J.M. 2004. Cold-water coral reefs. UNEP-WCMC, Cambridge, UK.

- Lance E. Morgan & Ratana Chuenpagdee, Shifting Gears: Addressing the Collateral Impacts of Fishing Methods in US Waters. Pew science series on conservation and the environment, 2003.

Différences entre les chaluts

Rumohr et al. 2000 décrivent ainsi la différence entre les chaluts à panneaux (otter trawls) et les chaluts à perche (beam trawls) : “Avec un chalut à panneaux, le bourrelet (filin lesté qui maintient le chalut en contact avec le fond) glisse sur le fond tandis que les panneaux labourent le substrat. Les chaluts à perche, quant à eux, utilisent des chaînes gratteuses (tickler chains) très lourdes pour chasser les poissons plats du sédiment où ils s’enfouissent. En conséquence de cela, les chaluts à panneaux ou à perche attrapent tous deux les poissons démersaux et les invertébrés, mais les chaluts à perche affectent également les animaux qui vivent dans la couche supérieure du sédiment. »

Les chaluts profonds ont une ouverture variant de 22 mètres pour les plus petits d’entre eux et jusqu’à 125 mètres.

Références

- Auster, P. J., Gjerde, K., Heupel, E., Watling, L., Grehan, A., and Rogers, A. D. 2011. Definition and detection of vulnerable marine ecosystems on the high seas: problems with the “move-on” rule. – ICES Journal of Marine Science, 68: 254–264.

- Angela R. Benn et al., Human Activities on the Deep Seafloor in the North East Atlantic: An Assessment of Spatial Extent. PLoS ONE, September 2010 | Volume 5 | Issue 9 | e12730.

Les impacts physiques des chaluts sur le fond marin

Ce sont essentiellement les panneaux qui creusent sillons et traces profondes sur le fond marin, même si les chaînes, les sphères, les bourrelets, les diabolos (les roues) et le filet lui-même laissent aussi des traces de leur passage. Les chaluts à perche et les dragues à coquilles nivellent en plus le fond marin. Le sédiment est perturbé sur une profondeur de quelques centimètres et jusqu’à un mètre pour les chaluts profonds. La largeur des sillons tracés par les panneaux est en moyenne de 80 cm.

Les recherches indiquent des résultats très variés sur la durée de persistance des impacts physiques causés par le chalut, allant de quelques minutes à plusieurs années. Cela dépend des milieux marins sur lesquels le chalut est déployé :

- Les fonds sableux : les traces persistent plusieurs jours.

- Les fonds vaseux : les traces sont visibles pendant au moins un an.

- Les monts sous-marins profonds : les traces persistent plusieurs années et possiblement plusieurs siècles.

La resuspension du sédiment

Pendant et après l’activité de chalutage, la resuspension est visible sous forme de nuages de sédiment. La présence de cette charge de sédiments dans la colonne d’eau ne dure pas forcément très longtemps. La durée dépend du substrat qui a été travaillé par le chalut, elle va de quelques minutes à plusieurs heures dans le cas des sédiments fins et jusqu’à plusieurs jours pour les fonds vaseux. L’augmentation de particules dans l’eau est de 1000%.

Découvrir les prises de vue aériennes de l’impact des chaluts de fond (pêches réalisées en eaux très peu profondes, c’est pour cela que le nuage de sédiment soulevé par les chaluts peut être photographié) : http://people.duke.edu/~ksv2/guest/

Dans les eaux de la surface, les changements causés au sédiment peuvent stimuler des explosions d’algues nocives.

Les effets de la resuspension sur la productivité des milieux marins sont estimés être très importants : la resuspension d’un seul millimètre de sédiment peut accroitre la productivité de l’environnement de 100 à 200%. C’est ainsi que la resuspension peut accélérer le recyclage des nutriments sur les marges continentales. On compare souvent les effets du chalutage aux perturbations naturelles, mais Thrush and Dayton (2002) ont spécifiquement adressé cet aspect en disant : “Il est inapproprié de comparer les perturbations causées par les tempêtes à celles induites par la pêche puisque cette dernière peut impliquer une intensité de perturbation bien plus importante”.

Les impacts sur la faune

Le chalutage cause une réduction de la biodiversité, de la richesse en espèces et taxons et de l’abondance. La recherché a montré que le chalutage créait « un changement vers une communauté plus homogénéisée » ainsi qu’une uniformité plus élevée sur les sites touchés en raison de la réduction en priorité des animaux les plus abondants.

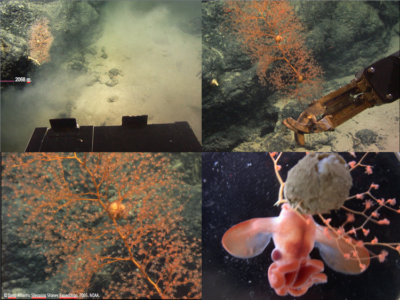

Les recifs coralliens

L’impact du chalutage profond sur les récifs coralliens profonds a été documenté en divers endroits, en Nouvelle Zélande, à l’Ouest de l’Irlande et particulièrement en Norvège et en Floride, où les récifs formés respectivement pas les espèces Lophelia et Oculina ont subi en très peu de temps d’immenses dommages. En Norvège, les chercheurs estiment que jusqu’à 50% des récifs ont été détruits partiellement ou totalement par le chalutage.

« Les chaluts de fond sont les plus destructeurs pour les coraux profonds, réalisant de véritables entailles, de plusieurs dizaines de cm de hauteur, à travers les massifs, par leur perche ou leurs panneaux. (…) Si certains monts carbonatés bien pentus sont peu propices à la pêche, les monts Darwin ne mesurent que 5 mètres de haut et sont plus susceptibles d’être endommagés. »

Karine Olu-Le Roy, Les coraux profonds : une biodiversité à évaluer et à préserver. VertigO – La revue en sciences de l’environnement, Vol 5 no 3, décembre 2004.

L’impact du chalutage profond sur les récifs d’Oculina varicosa à l’est de la Floride (uniquement connus à cet endroit) a été documenté au cours de plongées profondes en submersible. Des transects photographiques historiques ont été réalisés dès les années 1970, avant le développement substantiel de la pêche récréative et du chalutage commercial. Ils ont été comparés à des résultats de transects menés aux mêmes endroits en 2001, 25 ans plus tard. Entre-temps, la pêche avait causé les dégâts suivants :

« Dans les années 1970, les récifs d’Oculina grouillaient de bancs de mérous et de vivaneaux en période de frai. Au début des années 1990, la pêche commerciale et récréative avait décimé les populations de poissons, et les coraux avaient été sérieusement endommagés par le chalutage de fond. Des transects photographiques historiques, réalisés dans les années 1970 (…), fournissent une preuve cruciale de l’état et de la santé des récifs avant la pêche intensive et les activités de chalutage. Les analyses quantitatives des images photographiques révèlent des pertes drastiques de la couverture corallienne vivante entre 1975 et 2001. Six sites de récifs coralliens comptait près de 100% de perte de coraux vivants. »

Réf. Reed, John K; Koenig, Christopher C; Shepard, Andrew N, Impacts of bottom trawling on a deep-water Oculina coral ecosystem off Florida. Bulletin of Marine Science [Bull. Mar. Sci.]. Vol. 81, no. 2.

Les coraux solitaires

« Des engins de pêche destructrice, comme les chaluts de fond, les palangres et les casiers mettent en péril ces habitats fragiles. Les chaluts remontent à la surface des colonies pluricentenaires de coraux Paragorgia sp. comme « prises accessoires ». La pêche à la palangre casse et renverse des colonies de gorgones, provoquant leur disparition. Certains coraux précieux (Corallium sp.) et les coraux bambou (par exemple, Keratoisis sp.) sont récoltés directement pour le commerce des bijoux et des curiosités. Les pêcheries mettent en péril la survie des coraux profonds. »

Peter J. Etnoyer, Deep-Sea Corals on Seamounts. Oceanography Vol.23, No.1128

Remerciements spéciaux à Marleen Hoofd

Références

Références concernant l’impact des chaluts profonds : cliquer ici

Références concernant l’impact des chaluts en général : cliquer ici

- I. G. Priede et al., A review of the spatial extent of fishery effects and species vulnerability of the deep-sea demersal fish assemblage of the Porcupine Seabight, Northeast Atlantic Ocean (ICES Subarea VII). ICES Journal of Marine Science; doi:10.1093, June 2010.

- Alexander, Moore, Kendall. 1914. Otter-trawl fishery Report of the US Commissioner of Fisheries, Appendix V1.

- Aller. 1982. The effects of macrobenthos on chemical properties of marine sediment and overlying water. In: Animal-sediment relations. Call and Tevesz. Plenum Press, New York. 53-102. (Used in quote from Pilskaln et al. 1998.)

- Aller. 1988. Benthic fauna and biogeochemical processes in marine sediment: the role of burrow structures. In: Nitrogen cycling in coastal marine environments. Blackburn and Sorensen. J. Wiley and Sons, New York. (Used in quote from Pilskaln et al. 1998.)

- Althaus, Williams, Schlacher, Kloser, Green, Barker, Bax, Brodie, Schlacher-Hoenlinger. 2009. Impacts of bottom trawling on deep-coral ecosystems of seamounts are long-lasting. Marine Ecology Progress Series 397: 279-294.

- Angel, Rice. 1996. The ecology of the deep ocean and its relevance to global waste management. Journal of Applied Ecology 33:915-926. (Used in quote from Kaiser et al. 2002.)

- Anon. 1996. Report of the working group on ecosystem effects of fishing activities. ICES CM 1996/Assess/Env:1. (Used in quote from Tuck et al. 1998.)

- Ardizzone, Migliuolo. 1983. Modification of a Posidonia oceanica (L.) Delile prairie of the Mod-Tyrrhenian Sea after trawling activity. / Modificazioni di una prateria di Posidonia oceanica (L.) Delile del medio Tirreno sottoposta ad attività di pesca a strascico. Naturalista sicil. Suppl. IV:3:509-515

- Ardizzone, Pelusi. 1983. Regression of a Tyrrhenian Posidonia oceanica prairie exposed to near shore trawling. Rapports et Proces-Verbaux des Reunions Conseil International pour l’Exploration Scientifique de la Mer Mediterranee 28:3:175-177.

- Ardizzone, Tucci, Somaschini, Belluscio. 2000. Is bottom trawling partly responsible for the regression of Posidonia oceanica meadows in the Mediterranean Sea? In: Effects of fishing on non-target species and habitats: biological, conservation and socio-economic issues. M.J. Kaiser and S.J. de Groot. Blackwell Science Ltd. Oxford, UK. 37-46.

- Asch, Collie. 2008. Changes in a benthic megafaunal community due to disturbance from bottom fishing and the establishment of a fishery closure. Fishery Bulletin 106:4:438-456.

- Ault, Serafy, DiResta, Dandelski. 1997. Impacts of commercial fishing on key habitats within Biscayne National Park. Annual Report. Cooperative Agreement No. CA-5250-6-9018 iii.

- Auster, Malatesta, Langton, Watling, Valentine, Donaldson, Langton, Shepard, Babb. 1996. The impacts of mobile fishing gear on seafloor habitats in the Gulf of Maine (northwest Atlantic): Implications for conservation of fish populations. Reviews in Fisheries Science 4:2:185-202. (Used in quote from Kaiser et al. 2002.)

- Auster, Langton. 1999. The effects of fishing on fish habitat. Fish habitat: essential fish habitat and rehabilitation. American Fisheries Society, Symposium 22. Benaka. Bethesda, Maryland. 150-187.

- Ball, Munday, Tuck. 2000. Effects of otter trawling on the benthos and environment in muddy sediments. In: Effects of fishing on non-target species and habitats: biological, conservation and socio-economic issues. M.J. Kaiser and S.J. de Groot. Blackwell Science Ltd. Oxford, UK. 69-82.

- Bergman, Fonds, Hup, Stam. 1990. Direct effects of beamtrawl fishing on benthic fauna in the North Sea. ICES CM 1990/M INI:11. Copenhagen, Denmark. 19 p.

- Bergman, Hup. 1992. Direct effects of beamtrawling on macrofauna in a sandy sediment in the southern North Sea. ICES Journal of Marine Science 49:1:5-11

- Bergman, van Santbrink. 1994. Direct effects of beam trawling on macrofauna in a soft bottom area in the southern North Sea. Environmental impact of bottom gears on the benthic fauna in relation to natural resource management and protection of the North Sea. NIOZ Rapport 1994-11. RIVO-DLO Report CO 26/94. Netherlands Institute for Fisheries Research, Texel, The Netherlands. 179-208.

- Berkely, Pybas, Campos. 1985. Bait shrimp fishery of Biscayne Bay. Florida Sea Grant College Program Technical Paper No. 40. 16 p.

- Bhagirathan, Meenakumari, Jayalakshmy, Panda, Madhu, Vaghela. 2010. Impact of bottom trawling on sediment characteristics-a study along inshore waters off Veraval coast, India. Environmental Monitoring and Assessment 160:355-369.

- Boehlert, Yoklavich, Chelton. 1989. Time series of growth in the genus Sebastes from the Northeast Pacific Ocean. Fishery Bulletin 87:791–806. (Used in quote from Koslow et al. 2000.)

- Bradstock, Gordon. 1983. Coral-like bryozoan growths in Tasman Bay, and their protection to conserve commercial fish stocks. New Zealand Journal of Marine and Freshwater Research 17:2:159-163.

- Bremner, Frid, Rogers. 2005. Biological Traits of the North Sea Benthos: Does Fishing Affect Benthic Ecosystem Function? In: Benthic Habitats and the Effects of Fishing. Barnes and Thomas. America Fisheries Society, Bethesda, Maryland, USA. 477-489.

- Brown, Finney, Hills, Dommisse. 2005. Effects of commercial otter trawling on the physical environment of the southeastern Bering Sea. Continental Shelf Research 25:10:1281-1301.

- Brylinsky, Gibson, Gordon. 1994. Impacts of flounder trawls on the intertidal habitat and community of the Minas Basin, Bay of Fundy. Canadian Journal of Fisheries and Aquatic Sciences 51:3:650-661.

- Campbell, Officer, Prosser, Lawrence, Drabsch, Courtney. 2010. Survival of Graded Scallops Amusium balloti in Queensland’s (Australia) Trawl Fishery. Journal of Shellfish Research 29:2:2373-380.

- C. H. P. Unpublished data. (Used in quote from Pilskaln et al. 1998.)

- Christensen, Murray, Devol, Codispoti. 1987. Denitrification in continental shelf sediments has major impact on the oceanic nitrogen budget. Global Biogeochemical Cycles 1:97–116. (Used in quote from Pilskaln et al. 1998.)

- Churchill. 1989. The effect of commercial trawling on sediment resuspension and transport over the Middle Atlantic Bight continental shelf. Continental Shelf Research 9:841-864.

- Clark. 1995. Experience with the management of orange roughy (Hoplostethus atlanticus) in New Zealand, and the effects of commercial fishing on stocks over the period 1980–1993. In: Deep-water Fisheries of the North Atlantic Oceanic Slope. Hopper. Kluwer Academic Publishers, Dordrecht. 251-266. (Useed in quote from Koslow et al. 2000.)

- Clark. 1999. Fisheries for orange roughy (Hoplostethus atlanticus) on seamounts in New Zealand. Oceanologica Acta 22:593–602. (Used in quote from Koslow et al. 2000.)

- Clark, O’Driscoll. 2001. Deepwater fisheries and aspects of their impact on seamount habitat in New Zealand. Journal of Northwest Atlantic Fishery Science 31:441:458.

- Clark, Tracey. 1994. Changes in a population of orange roughy, Hoplostethus atlanticus, with commercial exploitation on the Challenger Plateau, New Zealand. Fishery Bulletin 92:236–253. (Used in quote from Koslow et al. 2000.)

- Clark, Fincham, Tracey. 1994. Fecundity of orange roughy (Hoplostethus atlanticus) in New Zealand waters. New Zealand Journal of Marine and Freshwater Research 28:193-200. (Used in quote from Koslow et al. 2000.)

- Collie, Escanero, Valentine. 1997. Effects of bottom fishing on the benthic megafauna of Georges Bank. Marine Ecology Progress Series 155:159-172.

- Collie, Hermsen, Valentine, Almeida. 2005. Effects of Fishing on Gravel Habitats: Assessment and Recovery of Benthic Megafauna on Georges Bank. In: Benthic Habitats and the Effects of Fishing. Barnes and Thomas. America Fisheries Society, Bethesda, Maryland, USA. 325-343.

- Collie, Hall, Kaiser, Poiner. 2000. Shelf sea fishing disturbance of benthos: trends and predictions. Journal of Animal Ecology 69:5:785-798.

- Connell. 1978. Diversity in tropical rain forests and coral reefs. Science 199:1302–1310. (Used in quote from Asch and Collie 2008.)

- Currie, Parry. 1996. Effects of scallop dredging on a sort sediment community: a large scale experimental study. Marine Ecology Progress Series 134:131-150. (Used in a quote from Tuck et al. 1998.)

- De Biasi. 2004. Impact of experimental trawling on the benthic assemblage along the Tuscany coast (North Tyrrhenian Sea, Italy). ICES Journal of Marine Science 61:8:1260-1266.

- De Groot. 1972. Some further experiments on the influence of the beam trawl on the bottom fauna. ICES Gear and Behaviour Committee. CM 1972/B:6. 7 p.

- De Juan, Demestre, Thrush. 2009. Defining ecological indicators of trawling disturbance when everywhere that can be fished is fished: A Mediterranean case study. Marine Policy 33:472-478.

- Dellapenna, Allison, Gill, Lehman, Warnken. 2006. The impact of shrimp trawling and associated sediment resuspension in mud dominated, shallow estuaries. Estuarine, Coastal and Shelf Science 69:3-4:519-530.

- Demestre, Sanches, Kaiser. 2000. The behavioural response of benthic scavengers to ottertrawling disturbance in the Mediterranean. In: Effects of fishing on non-target species and habitats: biological, conservation and socio-economic issues. M.J. Kaiser and S.J. de Groot. Blackwell Science Ltd. Oxford, UK. 121-129

- D’Onghia, Maiorano, Sion, Giove, Capezzuto, Carlucci, Tursi. 2010. Effects of deep-water coral banks on the abundance and size structure of the megafauna in the Mediterranean Sea. Deep-Sea Research II 57:397-411.

- Dounas, Davies, Triantafyllou, Koulouri, Petihakis, Arvanitidis, Soulatzis, Eleftheriou. 2007. Large-scale impacts of bottom trawling on shelf primary productivity. Continental Shelf Research 27:17:2198-2210.

- Drabsch, Tanner, Connell. 2001. Limited infaunal response to experimental trawling in previously untrawled areas. ICES Journal of Marine Science 58:1261-1271.

- Duplisea, Jennings, Malcolm, Parker and Sivyer. 2001. Modelling potential impacts of bottom trawl fisheries on soft sediment biogeochemistry in the North Sea. Geochemical Transactions 2:1:112-117.

- Durrieu de Madron, Ferre, Le Corre, Grenz, Conan, Pujo-Pay, Buscail, Bodiot. 2005. Trawling-induced resuspension and dispersal of muddy sediments and dissolved elements in the Gulf of Lion (NW Mediterranean). Continental shelf research 25:19-20:2387-2409.

- Engel, Kvitek. 1998. Impacts of otter trawling on a benthic community in Monterey Bay National Marine Sanctuary. Conservation Biology 12:6:1204-1214.

- Fanelli, Badalamenti, D’Anna, Pipitone. 2009. Diet and trophic level of scaldfish Arnoglossus laterna in the southern Tyrrhenian Sea (western Mediterranean): contrasting trawled versus untrawled areas. Journal of the Marine Biological Association of the United Kingdom 89:4:817-828.

- Fanning, Carder, Betzer. 1982. Sediment resuspension by coastal waters: a potential mechanism for nutrient recycling on the ocean’s margins. Deep-Sea Research 29:953–965.

- Fonteyne. 2000. Physical impact of beam trawls on seabed sediments. In: Effects of fishing on non-target species and habitats: biological, conservation and socio-economic issues. M.J. Kaiser and S.J. de Groot. Blackwell Science Ltd. Oxford, UK. 15-36.

- Freese, Auster, Heifetz, Wing. 1999. Effects of trawling on seafloor habitat and associated invertebrate taxa in the Gulf of Alaska. Marine Ecology Progress Series 182:119-126.

- Frid, Harwood, Hall, Hall. 2000. Long-term changes in the benthic communities on North Sea fishing grounds. ICES Journal of Marine Science 57:1303-1309. (Used in a quote from Kaiser et al. 2002.)

- Friedlander, Boehlert, Field, Mason, Gardner, Dartnell. 1999. Sidescansonar mapping of benthic trawl marks on the shelf and slope off Eureka, California. Fishery Bulletin 97:4:786-801.

- Gibbs, Collins, Collett. 1980. Effect of otter prawn trawling on the macrobenthos of a sandy substratum in a New-South-Wales Estuary. Australian Journal of Marine and Freshwater Research 31:4:509-516.

- Gilkinson, Paulin, Hurley, Schwinghamer. 1998. Impacts of trawl door scouring on infaunal bivalves: results of a physical trawl door model/dense sand interaction. Journal of Experimental Marine Biology and Ecology 244:2:291-312.

- Giovanardi, Pravoni, Franceschini. 1998. « Rapido » trawl fishing in the Northern Adriatic: preliminary observations of the effects on macrobenthic communities. Acta Adriatica 39:1:37-52.

- Graham. 1955. Effect of trawling on animals of the sea bed. Deep Sea Research Supplement 3:1-6.

- Greenstreet, Spence, McMillan. 1999. Fishing effects in northeast Atlantic shelf seas: patterns in fishing effort, diversity and community structure. Changes in the structure of the North Sea groundfish species assemblage between 1925 and 1996. Fisheries Research 40:2:153-183.

- Hall-Spencer, Allain, Fossa. 2002. Trawling damage to Northeast Atlantic ancient coral reefs. Proceedings of the Royal Society of London Series B-Biological Sciences 269:1490:507-511.

- Haedrich. 1995. Structure over time of an exploited deepwater fish assemblage. In: Deep-water Fisheries of the North Atlantic Oceanic Slope. Hopper. Kluwer Academic Publishers. (Used in quote from Koslow et al. 2000.)

- Hall-Spencer, Froglia, Atkinson, Moore. 1999. The impact of Rapido trawling for scallops, Pecten jacobaeus (L.), on the benthos of the Gulf of Venice. ICES Journal of Marine Science 56:1:111-124.

- Hannah, Jones, Miller, Knight. 2010. Effects of trawling for ocean shrimp (Pandalus jordani) on macroinvertebrate abundance and diversity at four sites near Nehalem Bank, Oregon. Fishery Bulletin 108:1:30-38.

- Hansson, Lindegarth, Valentinsson, Ulmestrand. 2000. Effects of shrimp-trawling on abundance of benthic macrofauna in Gullmarsfjorden, Sweden. Marine Ecology Progress Series 198:191-201.

- Heifetz, Stone, Shotwell. 2009. Damage and disturbance to coral and sponge habitat of the Aleutian Archipelago. Marine Ecology Progress Series 397:295-303.

- Hiddink, Rijnsdorp, Piet. 2008. Can bottom trawling disturbance increase food production for a commercial fish species? Canadian Journal of Fisheries and Aquatic Sciences 65:7:1393-1401.

- Hinz, Prieto, Kaiser. 2009. Trawl disturbance on benthic communities: chronic effects and experimental predictions. Ecological Applications 19:3:761-773.

- Huxley. 1883. Inaugural Address Fisheries Exhibition, London.

- Jennings, Dinmore, Duplisea, Warr, Lancaster. 2001. Trawling disturbance can modify benthic production processes. Journal of animal ecology 70:3:459-475.

- Jennings, Kaiser. 1998. The effects of fishing on marine ecosystems. Advances in Marine Biology 34:201-352. (Used in quote from Kaiser et al. 2002.)

- Jennings, Nicholson, Dinmore, Lancaster. 2002. Effects of chronic trawling disturbance on the production of infaunal communities. Marine ecology progress series 343:251-260.

- Jennings, Pinnegar, Polunin, Warr. 2001. Impacts of trawling disturbance on the trophic structure of benthic invertebrate communities. Marine Ecology Progress Series 213:127-142.

- Kaiser, Spencer. 1993b. A preliminary assessment of the immediate effects of beam trawling on a benthic community in the Irish Sea. ICES CM 1993/B:38 (REF E + L). 9 p.

- Kaiser, Spencer. 1994. Fish scavenging behavior in recently trawled areas. Marine Ecology Progress Series 112:41-49. (Used in quote from Langton and Auster 1999.)

- Kaiser, Spencer. 1996a. The effects of beam-trawl disturbance on infaunal communities in different habitats. Journal of Animal Ecology 65:348-358. (Used in quote from Tuck et al. 1998.)

- Kaiser, Spencer. 1996b. Behavioural responses of scavengers to beam trawl disturbance. In: Aquatic Predators and their Prey. Greenstreet and Tasker. Blackwell Scientific Publications, Oxford. 116-123.

- Kaiser, Ramsay. 1997. Opportunistic feeding by dabs within areas of trawl disturbance: Possible implications for increased survival. Marine Ecology Progress Series 152:1-3:307-310.

- Kaiser, Edwards, Armstrong, Radford, Lough, Flatt, Jones. 1998. Changes in megafaunal benthic communities in different habitats after trawling disturbance. ICES Journal of Marine Science 55:3:353-361.

- Kaiser, Rogers, Ellis. 1999. Importance of benthic habitat complexity for demersal fish assemblages. In: Fish habitat: essential fish habitat and rehabilitation. American Fisheries Society, Symposium 22. Benaka. Bethesda, Maryland. (Used in quote from Kaiser et al. 2002.)

- Kaiser, Spence, Hart. 2000a. Fishinggear restrictions and conservation of benthic habitat complexity. Conservation Biology 14:5:1512-1525.

- Kaiser, Ramsay, Richardson, Spence, Brand. 2000b. Chronic fishing disturbance has changed shelf sea benthic community structure. Journal of Animal Ecology 69:3:494-503.

- Kaiser, Collie, Hall, Jennings, Poiner. 2002. Modification of marine habitats by trawling activities: prognosis and solutions. Fish and Fisheries 3:2:114-136.

- Koslow, Gowlett-Holmes, Lowry, O’Hara, Poore, Williams. 2001. Seamount benthic macrofauna off southern Tasmania: community structure and impacts of trawling. Marine Ecology Progress Series 213:111-125.

- Koslow, Gowlett-Holmes. 1998. The seamount fauna off southern Tasmania: benthic communities, their conservation and impacts of trawling. Final Report to Environment Australia and the Fisheries Research Development Corporation. 104 pp. (Used in a quote from Koslow et al. 2000.)

- Koslow, Bell, Virtue, Smith. 1995. Fecundity and its variability in orange roughy: effects of population density, condition, egg size, and senescence. Journal of Fish Biology 47:1063–1080 (Used in quote from Koslow et al. 2000.)

- Koslow, Boehlert, Gordon, Haedrich, Lorance, Parin. 2000. Continental slope and deep-sea fisheries: implications for a fragile ecosystem. ICES Journal of Marine Science 57:3:548-557.

- Koulouri, Dounas, Eleftheriou. 2005. Preliminary results on the effect of otter trawling on hyperbenthic communities in Heraklion Bay (Eastern Mediterranean, Cretan Sea). In: Benthic Habitats and the Effects of Fishing. Barnes and Thomas. America Fisheries Society, Bethesda, Maryland, USA. 529-537.

- Krost. 1990. The impact of otter-trawl fishery on nutrient release from the sediment and macrofauna of Kieler Bucht (western Baltic). Ph.D. dissertation. Berichte aus dem Institut fur Meereskunde an der Christian-Albrechts-Universitat Kiel. Kiel. 200, 160 pp.

- Krost. 1993. The significance of the bottomtrawl fishery for the sediment, its exchange processes, and the benthic communities in the bay of Kiel. Arbeiten des Deutschen Fischerei-Verbandes 57:43-60.

- Laban, Lindeboom. 1991. Penetration depth of beamtrawl gear. In: Effects of Beamtrawl Fishery on the Bottom Fauna in the North Sea, II: the 1990 studies. BEONRAPPORT 13. Netherlands Institute for Sea Research, Texel, The Netherlands. 37-52.

- Langton, Auster. 1999. Marine fishery and habitat interactions: to what extent are fisheries and habitat interdependent. Fisheries 24:6:14-21.

- Large, Lorance, Pope. 1998. The survey estimates of the overall size composition of the deepwater fish species on the European continental slope, before and after exploitation. ICES CM 1998/O: 24. (Used in quote from Koslow et al. 2000.)

- Leaman. 1991. Reproductive styles and life history variables relative to exploitation and management of Sebastes stocks. Environmental Biology of Fishes 30:253–271. (Used in quote from Koslow et al. 2000.)

- Laurenson, Unsworth, Penn, Lenanton. 1993. The impact of trawling for saucer scallops and western king prawns on the benthic communities in coastal waters off south Western Australia. Fisheries Research Report No. 100. Fisheries Department of Western Australia. 93 p.

- Ligas, De Biasi, Demestre, Pacciardi, Sartor, Cartes. 2009. Effects of chronic trawling disturbance on the secondary production of suprabenthic and infaunal crustacean communities in the Adriatic Sea (NW Mediterranean). Ciencias Marinas 35:2:195-207.

- Lindeboom, de Groot. 1998. Impact II: The Effects of Different Types of Fisheries on the North Sea and Irish Sea Benthic Ecosystems. NIOZ-RAPPORT 1998-1/RIVO-DLO REPORT C003/98. Netherlands Institute for Sea Research. Texel, The Netherlands.

- Lorance. 1998. Structure du peuplement ichthyologique du talus continental à l’ouest des Iles Britanniques et impact de la pêche. Cybium 22:209–231. (Used in a quote from Koslow et al. 2000.)

- Mayer, Schick, Findlay, Rice. 1991. Effects of commercial dragging on sedimentary organic matter. Marine Environmental Research 31:4:249-261.

- McConnaughey, Mier, Braxton. 2000. An examination of chronic trawling effects on soft-bottom benthos of the eastern Bering Sea. ICES Journal of Marine Science 57:1377-1388.

- Merrett, Haedrich. 1997. Deep-Sea Demersal Fish and Fisheries. Chapman and Hall, London. 282 pp. (Used in quote from Koslow et al. 2000.)

- Meyer, Fonseca, Murphey, McMichael, Terly, LaCroix, Whitfield, Thayer. 1999. Effects of live-bait shrimp trawling on seagrass beds and fish bycatch in Tampa Bay, Florida. Fishery Bulletin 97:1:193-199.

- Mullineaux, Mills. 1997. A test of the larval retention hypothesis in seamount-generated flows. Deep-Sea Research 44:745–770. (Used in quote from Koslow et al. 2000.)

- Norse, Watling. 1999. Impacts of mobile fishing gear: the biodiversity perspective. Fish habitat: essential fish habitat and rehabilitation. American Fisheries Society, Symposium 22. Benaka. Bethesda, Maryland. 31-40.

- Olsgard, Schaanning, Widdicombe, Kendall, Austen. 2008. Effects of bottom trawling on ecosystem functioning. Journal of Experimental Marine Biology and Ecology 366:1-2:123-133.

- Piet, Rijnsdorp. 1998. Changes in the demersal fish assemblage in the south-eastern North Sea following the establishment of a protected area ( »plaice box »). ICES Journal of Marine Science 55:420-429.

- Palanques, Guillen, Puig. 2001. Impact of bottom trawling on water turbidity and muddy sediment of an unfished continental shelf. Limnology and oceanography 46:5:1100-1110.

- Parker, Tunnicliffe. 1994. Dispersal strategies of the biota on an oceanic seamount: implications for ecology and biogeography. Biological Bulletin 187:336–345. (Used in quote from Koslow et al. 2000.)

- Paschen, Richter, Köpnick. 1999. Trawl Penetration in the Seabed (TRAPESE). Draft Final Report EC-Study Contract No. 96–006. (Used in quote from Rose et al. 2000.)

- Pilskaln, Churchill, Mayer. 1998. Resuspension of sediment by bottom trawling in the Gulf of Maine and potential geochemical consequences. Conservation Biology 12:6:1223-1229.

- Pitcher, Burridge, Wassenberg, Hill, Poiner. 2009. A large scale BACI experiment to test the effects of prawn trawling on seabed biota in a closed area of the Great Barrier Reef Marine Park, Australia. Fisheries Research 99:168-183.

- Poiner, Blaber, Brewer, Burridge, Caeser, Connell, Dennis, Dews, Ellis, Farmer, Glaister, Gribble, Hill, O’Connor, Milton, Pitcher, Salini, Taranto, Thomas, Toscas, Wang, Veronise, Wassenberg. 1998. Final report on the effects of prawn trawling in the far northern section of the Great Barrier Reef: final report to Great Barrier Reef Marine Park Authority and Fisheries Research and Development Corporation on 1991-96 (years 1-5) research. CSIRO Marine Laboratories. (Used in quote from Kaiser et al. 2002.)

- Polymenakou, Paraskevi, Pusceddu, Tselepides, Polychronaki, Giannakourou, Fiordelmondo, Hatziyanni, Danovaro. 2005. Benthic microbial abundance and activities in an intensively trawled ecosystem (Thermaikos Gulf, Aegean Sea). Continental Shelf Research 25:19-20:2570-2584.

- Prena, Schwinghamer, Rowell, Gordon, Gilkinson, Vass, McKeown. 1999. Experimental otter trawling on a sandy bottom ecosystem of the Grand Banks of Newfoundland: analysis of trawl bycatch and effects on epifauna. Marine Ecology Progress Series 181:107-124.

- Probert, KcKnight, Grove. 1997. Benthic invertebrate by-catch from a deepwater trawl fishery, Chatham Rise, New Zealand. Aquatic Conservation: Marine and Freshwater Ecosystems 7:27–40. (Used in quote from Koslow et al. 2000.)

- Pusceddu, Fiodelmondo, Polymenakou, Polychronaki, Tselepides, Danovaro. 2005. Effects of bottom trawling on the quantity and biochemical composition of organic matter in coastal marine sediments (Thermaikos Gulf, northwestern Aegean Sea). Continental Shelf Research 25:19-20:2491-2505.

- Queiros, Hiddink, Kaiser, Hinz. 2006. Effects of chronic bottom trawling disturbance on benthic biomass, production and size spectra in different habitats. Journal of Experimental Marine Biology and Ecology 335:1:91-103.

- Ragnarsson, Lindegarth. 2009. Testing hypotheses about temporary and persistent effects of otter trawling on infauna: changes in diversity rather than abundance. Marine Ecology Progress Series 385:51-64

- Ramirez-Llodra, Company, Sarda, Rotllant. 2010. Megabenthic diversity patterns and community structure of the Blanes submarine canyon and adjacent slope in the Northwestern Mediterranean: a human overprint? Marine Ecology 31:1:167-182.

- Ramsay, Kaiser, Rijnsdorp, Craeymeersch, Ellis. 2000. Impact of trawling on populations of the invertebrate scavenger Asterias rubens. In: Effects of fishing on non-target species and habitats: biological, conservation and socio-economic issues. Kaiser and de Groot. Blackwell Science Ltd. Oxford, UK. 151-162.

- Reeves, DiDonato. 1972. Effects of trawling in Discovery Bay, Washington. Washington Department of Fisheries Technical Report No. 8. 45 p.

- Reise. 1982. Long term changes in the macrobenthic invertebrate fauna of the Wadden Sea: Are polychaetes about to take over? Netherlands Journal of Sea Research 16:29-36.

- Richer de Forges. 1998. La Diversité du Benthos Marin de Nouvelle-Caledonie: de l’Espèce a la Notion de Patrimonine. PhD thesis. Museum National d’Histoire Naturelle, Paris. 326 pp. (Used in quote from Koslow et al. 2000.)

- Riemann, Hoffmann. 1991. Ecological consequences of dredging and bottom trawling in the Limfjord, Denmark. Marine Ecology Progress Series 69:1-2:171-178.

- Roberts, Harvey, Lamont, Gage. 2000. Seabed photography, environmental assessment and evidence for deep-water trawling on the continental margin west of the Hebrides. Hydrobiologia 441:173-183.

- Rose, Carr, Ferro, Fonteyne, MacMullen. 2000. Using gear technology to understand and reduce unintended effects of fishing on the seabed and associated communities: background and potential directions. In ICES Working Group on Fishing Technology and Fish Behavior report, ICES CM 2000/B:03.

- Rumohr, Kujawski. 2000. The impact of trawl fishery on the epifauna of the southern North Sea. ICES Journal of Marine Science 57:5:1389-1394.

- Rumohr, Schomann, Kujawski. 1994. Environmental impact of bottom gears on benthic fauna in the German Bight. In: NIOZ Rapport 1994-11, Netherlands Institute for Fisheries Research, Texel. 75-86.

- Sainsbury. 1987. Assessment and management of the demersal fishery on the continental shelf of northwestern Australia. In: Tropical Snappers and Groupers – Biology and Fisheries Management. Polovina and Ralston). Westview Press, Boulder, Colorado. 465-503.

- Sainsbury, Campbell, Whitelaw. 1993. Effects of trawling on the marine habitat on the north west shelf of Australia and implications for sustainable fisheries management. In: Sustainable Fisheries through Sustainable Fish Habitat. Bureau of Resource Sciences Publication. Australian Government Publishing Service. Canberra, Australia. 137-145.

- Schratzberger, Lampadariou, Somerfield, Vandepitte, Vanden Berghe. 2009. The impact of seabed disturbance on nematode communities: linking field and laboratory observations. Marine Biology 156:709-724.

- Schwinghamer, Gordon, Rowell, Prena, McKeown, Sonnigchsen, Guignes. 1998. Effects of experimental otter trawling on surficial sediment properties of a sandy-bottom ecosystem on the Grand Banks of Newfoundland. Conservation Biology 12:6:1215:1222.

- Schwinghamer, Guigne, Siu. 1996. Quantifying the impact of trawling on benthic habitat structure using high resolution acoustics and chaos theory. Canadian Journal of Fisheries and Aquatic Science 53:288-296. (Used in quote from Kaiser et al. 2002.)

- Service, Magorrian. 1997. The extent and temporal variation of disturbance to epibenthic communities in Strangford Lough, Northern Ireland. Journal of the Marine Biological Association of the United Kingdom 77:4:1151-1164.

- Smith, Papadopoulou, Diliberto. 2000. Impact of otter trawl on eastern Mediterranean commercial trawl fishing ground. ICES Journal of Marine Science 57:1340-1351.

- Sparks-McConkey, Watling. 2001. Effects on the ecological integrity of a soft-bottom habitat from a trawling disturbance. Hydrobiologia 456:73-85.

- Steneck. 1997. Fisheries-induced biological changes to the structure and function of the Gulf of Maine. In: Proceedings of the Gulf of Maine Ecosystem Dynamics Scientific Symposium and Workshop. RARGOM Report, 91 – 1. Wallace and Braasch. Regional Association for Research on the Gulf of Maine. Hanover, NH. 151-165. (Used in quote from Thrush and Dayton 2002.)

- Svane, Hammett, Lauer. 2009. Impacts of trawling on benthic macro-fauna and -flora of the Spencer Gulf prawn fishing grounds. Estuarine, Coastal and Shelf Science 82:4:621-631.

- Thrush, Dayton. 2002. Disturbance to marine benthic habitats by trawling and dredging: implications for marine biodiversity. Annual Review of Ecology and Systematics 33:449-473.

- Trimmer, Peterson, Sivyer, Mills, Young, Parker. 2005. Impact of long-term benthic trawl disturbance on sediment sorting and biogeochemistry in the southern North Sea. Marine Ecology Progress Series 298:79-94.

- Tuck, Hall, Robertson, Armstrong, Basford. 1998. Effects of physical trawling disturbance in a previously unfished sheltered Scottish sea loch. Marine Ecology Progress Series 162:227-242.

- Turner, Thrush, Hewitt, Cummings, Funnell. 1999. Fishing impacts and the degradation or loss of habitat structure. Fisheries Management and Ecology 6:5:401-420.

- Van Dolah, Wendt, Nicholson. 1987. Effects of a research trawl on a hard-bottom assemblage of sponges and corals. Fisheries Research 5:1:39-54.

- Van Dolah, Wendt, Vonlevisen. 1991. A study of the effects of shrimp trawling on benthic communities in 2 South Carolina sounds. Fisheries Research 12:2:139-156.

- Van Santbrink, Bergman. 1994. Direct effects of beam trawling on macrofauna in a soft bottom area in the southern North Sea. Environmental impact of bottom gears on the benthic fauna in relation to natural resource management and protection of the North Sea. NIOZ Rapport 1994-11. RIVO-DLO Report CO 26/94. Netherlands Institute for Fisheries Research, Texel. 147-178.

- Vergnon, Blanchard. 2006. Evaluation of trawling disturbance on macrobenthic invertebrate communities in the Bay of Biscay, France: Abundance Biomass Comparison (ABC method). Aquatic Living Resources 19:3:219-228.

- Waller, Watling, Auster, Shank. 2007. Anthropogenic Impacts On the Corner Rise Seamounts, North-West Atlantic Ocean. Journal of the Marine Biological Association of the United Kingdom 87:1075-1076.

- Wassenberg, Dews, Cook. 2002. The impact of fish trawls on megabenthos (sponges) on the north-west shelf of Australia. Fisheries Research 58:2:141-151.

- Witman, Sebens. 1992. Regional variation in fish predation intensity: a historical perspective in the Gulf of Maine. Oecologia 90:305-15. (Used in quote from Thrush and Dayton 2002.)

- Wheeler, Bett, Billett, Masson, Mayor. 2005. The Impact of Demersal Trawling on NE Atlantic Deep-Water Coral Habitats: the Darwin Mounds, U.K. In: Benthic Habitats and the Effects of Fishing. Barnes and Thomas. America Fisheries Society, Bethesda, Maryland, USA. 807-817.

- Williams, Schlacher, Rowden, Althaus, Clark, Bowden, Stewart, Bax, Consalvey, Kloser. 2010. Seamount megabenthic assemblages fail to recover from trawling impacts. Marine Ecology